Emotionally targeted ads make consumers spend more — unless they know they’re being targeted

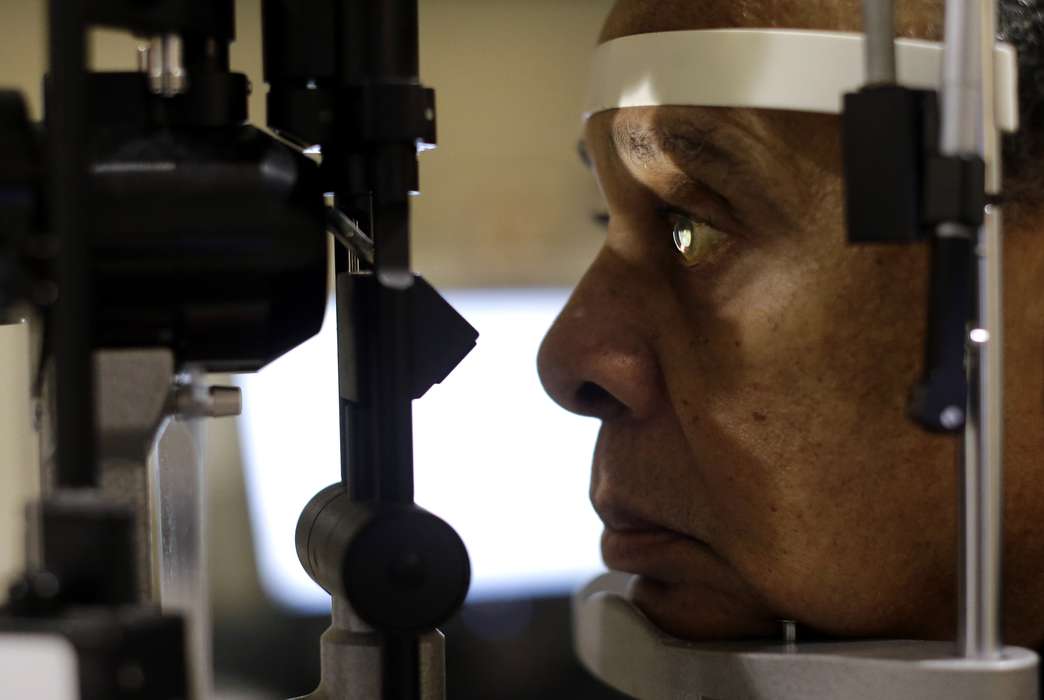

Targeted ads work ... as long as the targets don't know they're targets. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

In-store ads that target customers using facial recognition technology to detect their moods can increase sales and positive brand perceptions for retailers, potentially giving brick-and-mortar stores a way to compete with increasingly dominant online retailers like Amazon, according to a new study by three Austrian researchers.

However, the positive effect only exists if customers do not know their emotions are being monitored — meaning regulations that require retailers to disclose the use of emotional targeting technology would effectively eliminate its utility, the researchers said in a forthcoming article for the Journal of Business Research.

The findings about individuals’ privacy preferences within brick-and-mortar stores come in stark contrast to consumer behavior on the internet, where people are routinely tracked and served targeted ads based on individualized browsing and purchase data.

“We give so much information when we surf the web,” said co-author Marion Garaus, a professor of international management at Modul University in Vienna. “But when it comes to brick-and-mortar retailing, we do not want to give any personal data away.”

Garaus wrote the paper alongside Udo Wagner of the University of Vienna and Ricarda Rainer of the Austrian marketing consultancy Marketmind GmbH.

The researchers focused in particular on messages displayed on in-store digital signage systems, a market they say is worth more than $20 billion.

In order to measure the effectiveness of targeting the messages based on shoppers’ emotional states, the researchers conducted two experiments. The first was completed with in-person subjects prior to the coronavirus pandemic, while the second was conducted online because of lockdown-related constraints — namely, that researchers can’t detect subjects’ emotions when they’re wearing masks.

The first experiment, which used 194 participants, began by showing subjects either a happy or sad music video to influence their mood.

The happy music video was “Happy” by Pharrell, which the researchers wrote “shows many people of different age groups and ethnic backgrounds simply dancing happily in different life situations.” The sad music video was “Farewell” by Xavier Naidoo, which tells the story of a young man who commits suicide and features depressive visuals, including dark cliffs and a black-colored sea.

“After a comprehensive search, we identified that music is a good means to put shoppers in a certain mood state,” said Garaus.

After viewing either the happy or sad music video, the participants were shown a variety of advertisements for various grocery products, including “hedonic” items, such as chocolate, and “utilitarian” products, such as detergent. One ad for each product was “emotional,” depicting scenes like family events and pets. Another ad was “informative,” depicting the manufacturing and transport process behind each product. The subjects were then asked questions to gauge whether they liked a given product, as well as how much they would pay for it.

Subjects who had seen the happy music video, and were therefore presumed to be in a more positive mood, responded better to emotional ads for hedonic products, while subjects who were assumed to be in a negative mood preferred informative ads for the same hedonic products. For utilitarian products, participants in positive mood states reported higher product quality perceptions of both ad types in comparison to those in a negative mood.

After submitting a write-up of the first experiment to journals, reviewers asked the researchers to conduct additional research about whether disclosing the use of emotion-monitoring technology would impact customers’ habits. Since the request coincided with the first COVID-19 lockdown in Austria, the researchers moved the study online, finding 401 German subjects through the microtasking platform Clickworker.com.

At the beginning of the second study, subjects were asked to recall and briefly describe a situation that either made them feel happy or sad, and to focus on their emotions when recalling the memory. They were then asked to imagine themselves on a routine trip to their grocery store and shown images orange juice on a store shelf. The researchers chose orange juice because they considered it to be a “neutral,” rather than hedonic or utilitarian, product.

Alongside the images of the grocery store shelf, half of the subjects were shown a sign with the text, “We [the company] use facial recognition software in our branches. We don’t identify people; we only identify shoppers’ demographic (age, gender) and biometric (emotions) characteristics.” Then, the subjects were shown “emotional” and “informative” ads for an orange juice brand and took a survey to gauge their perceptions of the brand.

Subjects who had seen the disclosure about emotional targeting responded less positively to the advertisements than those who had not, meaning that including a disclosure effectively eliminates the effects of emotional targeting, the researchers said.

“Once they are aware of emotional targeting, then this whole strategy backfires,” said Garaus.

Overall, the study shows that emotional targeting is only effective if regulators do not require retailers to disclose its use, the researchers said.

While this study focused on grocery stores, the researchers added that they would like to see similar studies examining other brick-and-mortar stores.

“We could think about the fashion industry as well, or many other retailers,” said Wagner.

Garaus added that they would also like to examine attitudes toward emotional targeting technology in other regions, especially Asia.

“We [in Europe] are not willing to give our private information to any retailers or marketer,” Garaus said. “It would be very interesting to replicate the study also in other cultures.”

Tolerance of invasive test-and-tracing techniques that researchers say have saved hundreds of thousands of lives in countries like China and South Korea show that Asian consumers may have different attitudes than Europeans toward invasive marketing techniques, Garaus said.

The paper, titled “Emotional targeting using digital signage systems and facial recognition at the point-of-sale,” is forthcoming in the Journal of Business Research. The co-authors are Marion Garaus of MODUL University, Udo Wagner of the University of Vienna and Ricarda Rainer of Marketmind GmbH.