Democracy now threatened at its roots, according to wide-ranging anthropological analysis

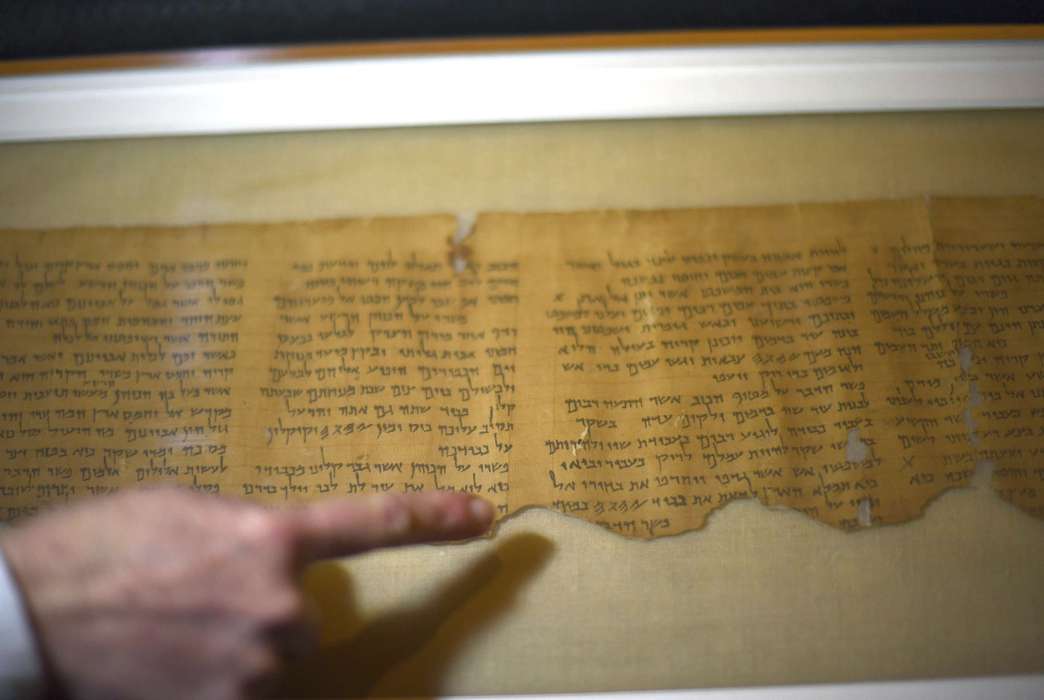

Democratic precepts are older than we think. (AP Photo/Bela Szandelszky)

“Good governments” with democratic features existed long before the dawn of modern society and were built on many of the same social and political bases as contemporary democracies, according to sweeping new historical research, a finding that could shed light on the causes of present-day “backsliding” in democracies around the world.

An article published Feb. 17 in Current Anthropology found evidence that across the world, a group of premodern states independently converged on taxation, bureaucratic and governing practices that allowed for meaningful participation by citizens, forming “good governments” with elements now commonly associated with liberal democracy.

The findings indicate that democratic governance doesn’t rest on individual rulers or on specific Enlightenment ideals but instead on building blocks of equitable taxation, public infrastructure investments and checks on rulers’ power over important resources — pillars which may be eroding in modern democracies, according to authors Richard Blanton, Lane Fargher, Gary Feinman and Stephen A. Kowalewski.

Their research bolsters the view that, "Contemporary democracies are threatened by economic and political forces that undercut the fiscal foundations of good government while strengthening the link between concentrated private wealth and the political process,” they wrote.

The researchers added that their work may help explain an “unexpected and difficult-to-explain decline” in many of the world’s modern-day democracies, ranging from serious backsliding in Turkey and Venezuela to signs of “slippage” even in the United States.

Political scientists studying backsliding “don’t seem to have a good idea of why democracies are failing all over the world,” Blanton told The Academic Times, citing an overall lack of convincing explanations of the phenomenon in the existing literature.

He and the other researchers already had experience using cross-cultural comparative methods to study the economic and political conditions that led to democratic governance in the premodern world, finding evidence in past research that countries reliant on revenue from a broad tax base generally adopt "good governance" practices.

That dynamic operated across a huge range of cultural, environmental and technological contexts, Blanton said, leading he and his colleagues to investigate whether it could shed light on what makes democracies tick.

Their analysis of 30 premodern societies from Asia to West Africa and Europe unearthed an extraordinary degree of commonality among the minority of governments able to provide good democratic governance.

Then, as now, "good government" was rare, with only 27% of the sample notching relatively high scores on good governance metrics, such as whether a country provided for public goods, equitable taxation and citizen voice, as well as controls over its rulers. By comparison, 40% logged consistently low scores on these metrics, according to the researchers.

Freedom House research from 2020 found that only about 43% of today's nation-states scored highly on measures of political rights and civil liberties, meeting the organization's criteria for "free" polities.

Nevertheless, a template seemed to emerge for the foundations of stable, democratic governance: Checks on ruler power, bureaucratic reform and public goods “tend to co-occur as a pattern of relatively good government,” the researchers wrote, adding that all three were typically absent among more autocratic regimes.

The pattern they unearthed suggests that democracy doesn’t arise only where culturally specific ideas or values hold sway; it can also appear where economic and political conditions encourage governments to accommodate citizens’ voices and provide them with stable infrastructure and other basic goods.

The “fiscal economy [of good governments means] that the resources that the state uses come from the people, they come from taxpayers paying for the costs of the state” rather than from the private wealth of the ruling class, Blanton said.

“If you get that kind of situation, then leadership has to acknowledge the will of the people and cut their own authority,” he added.

The need for egalitarian tax policy, robust infrastructure investment and limits on private money in government has been called into question in recent decades, the researchers argued, citing the rise of “market fundamentalist” ideologies advocating extremely limited government and economic deregulation.

“The market fundamentalism that was ushered in with President Reagan, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan and [UK] Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher during the 1980s encouraged people to pursue financial self-interest with no restraint or regulation,” Feinman told Phys.org.

As the fundamentals historically associated with good government are eroded, they said, it isn’t surprising to see some of today’s democracies falter.

“We need to bring economics and politics back into alignment so that we can better address the issue of private wealth and sectorial wealth on the political process,” Blanton said. “If you rob a polity of its tax base, you can’t maintain a democracy.”

The article “The Fiscal Economy of Good Government: Past and Present,” published Feb. 17 in Current Anthropology, was co-authored by Richard E. Blanton, Purdue University; Lane F. Fargher, Instituto Politécnico Nacional–Unidad Mérida; Gary M. Feinman, Field Museum of Natural History; Stephen A. Kowalewski, University of Georgia.