Stink bugs could be stopped by engineered pheromones

Pheromones might, ironically, be the secret to keeping stink bugs at bay. (Dorothea Tholl)

Stink bugs feast upon crops around the U.S. and are notoriously difficult to control with traditional pesticides. However, scientists at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University are seeking a patent for a potentially more effective — and greener — strategy, which involves luring the bugs away with pheromones produced by genetically engineered microbes and plants.

So far, the team has modified tobacco plants to produce enzymes that in two stink bug species are involved in the process of making pheromones. The patent application for the approach was published by the World Intellectual Property Organization on March 4.

Stink bugs are "a significant threat in agriculture and a real problem for a variety of different crops; those could be commodity crops — maize or soybean — but also specialty crops such as fruit trees," said Dorothea Tholl, a professor of biological sciences and co-inventor of the process. "We really see the need to better control these pests."

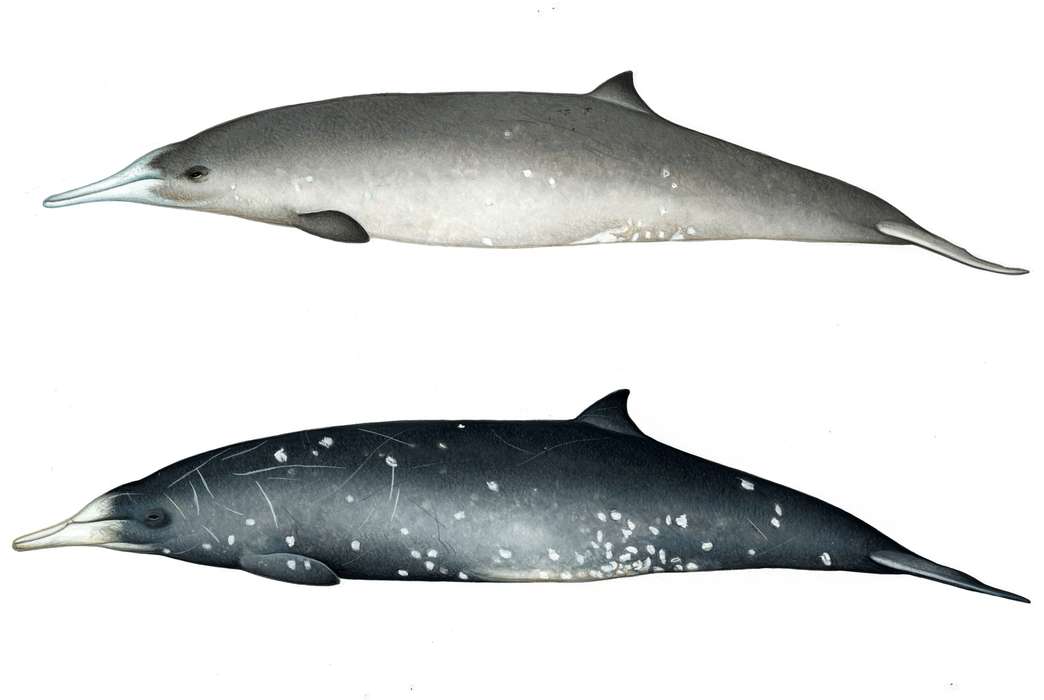

The invasive brown marmorated stink bug is a problem in the mid-Atlantic region, and has been observed feeding on a wide variety of fruits, vegetables and field crops, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Another species, the harlequin stink bug, is found on cabbage and related crops such as broccoli and kale in the southern half of the country and other regions with similar climates.

"If not controlled, the harlequin stink bug can easily destroy [an] entire crop by injuring the host plants by sucking their sap and causing them to wilt and die," Tholl and her co-inventor Jason Lancaster, a research associate, wrote in the patent application.

Unfortunately, the pesticides that work against caterpillars and other common pests often don't affect stink bugs, Tholl says. An alternative approach is to set out pheromone traps, which use chemicals that the insects normally release to communicate with each other to draw them away from vulnerable plants or disrupt their mating.

However, scientists have reported that conventional methods for making the pheromones often involve expensive, hazardous chemicals and lead to toxic waste byproducts. Using living organisms to build the chemicals is an appealing alternative.

"There's a huge market globally for pheromones, and developing these more environmentally friendly production platforms [is] something that we are interested in," Tholl said.

Stink bug pheromones are generally not the foul-smelling defense compounds the insects release when disturbed. Male stink bugs produce pheromones that attract both male and female insects, Tholl says. The pheromones belong to a larger class of compounds called terpenes that plants, fungi, bacteria and insects use for various purposes such as attracting pollinators or mates and repelling predators. Many of the essential oils extracted from plants get their aromas from terpenes like menthol.

"If we understand how these pheromones are made in insects, we can also use these genes and pathways and engineer them into plants," Tholl said. One application she and Lancaster outline in the patent is planting "trap crops" engineered to release pheromones that attract stink bugs. Alternatively, engineered plants or microbes such as yeast could be used as "factories" to produce the chemicals for pheromone traps.

Tholl's team has determined the first step of the pheromone production process in marmorated and harlequin stink bugs, which involves enzymes called terpene synthases. The researchers identified stink bug genes that, when expressed in E. coli, caused the bacteria to produce the terpene synthases. When the team prevented stink bugs from expressing these genes, the insects were unable to make their pheromones.

Once the researchers had confirmed the importance of these enzymes for pheromone production, they engineered tobacco plants to produce the terpene synthases found in marmorated and harlequin stink bugs.

The researchers are now investigating which other enzymes are involved in the next stage of pheromone production.

"We are at the first step of the pathway, but luckily these pathways can be just two enzymatic steps, or maybe three," Tholl said. "With our stink bugs we are lucky that the pathways are relatively simple."

Eventually, the team hopes to engineer plants and microbes capable of producing the pheromones. One particular advantage of planting trap crops in fields or orchards is that farmers would not need to reapply the bug-attracting chemicals the way they would with pheromone traps.

"Our plants," Tholl said, "would ideally release the pheromones for a longer time period."

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture provided funding for the research and has "certain rights in the invention," the application states.

The application for the patent, "Brown marmorated and harlequin stink bug pheromone enzyme synthesis and uses thereof," was filed Aug. 21, 2020, to the World Intellectual Property Organization. It was published March 4, 2021 with the application number PCT/US2020/047538. The earliest priority date was Aug. 23, 2019. The inventors of the pending patent are Dorothea Tholl and Jason Lancaster, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. The assignee is Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Parola Analytics provided technical research for this story.