What does your sweat say about your emotions?

What is your sweat telling the world? (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

By smelling the sweat of other people, humans can differentiate between sweat that results from fearful or neutral situations, a new study proved, though it's more difficult to determine the level of fear a person is feeling based on sweat alone.

In a paper published March 22 in Psychological Science, an international group of neuroscientists studied whether humans are capable of communicating their level of fear to another person through just the smell of their sweat.

It's known that body odors can transmit social information. And physiological changes in the person sweating, such as heart and breathing rates, impact the quality and quantity of odor molecules emitted through sweat. This can give other people, or "receivers," cues about the "sender's" internal state.

The study found that sweat emitted at different levels of fear all caused receivers to detect fear over other emotions, even with very small doses of sweat. This was the first study to confirm that fear sweat gives off volatile molecules that can travel through an olfactometer — an instrument that detects and measures odor dilution — and reach a participant's nose.

Jasper de Groot, an assistant professor at Radboud University, in the Netherlands, and a co-author of the paper, explained to The Academic Times that humans find it difficult to describe smells because "there is a disconnect between language and the smell experience." So in order to analyze the effects of scents on people, it's beneficial to use indirect measures, such as facial-muscle activity, while the subject is smelling something.

Previous studies have already demonstrated that a person experiencing fear emits sweat with qualitatively different molecules than happy and neutral people do. Specifically, fear-odor processing engages the amygdala and fusiform gyrus regions of the brain, both of which are associated with processing fearful faces.

For the current study, the researchers investigated whether different levels of fear odor are capable of inducing fear-specific responses when compared with neutral, nonfearful sweat. They also analyzed whether increasing levels of fear odor in sweat would have a greater impact on the behavioral, physiological and neural responses in the receiver participants.

In the other senses, stimulus strength is proved to be proportionate to emotional intensity. Injuries from sharper objects elicit more pain, and louder growls from animals elicit more fear, for example.

"Humans can decode different emotional intensities in faces and voices, yet evidence is lacking for such a phenomenon in the olfactory domain," the authors said in the paper.

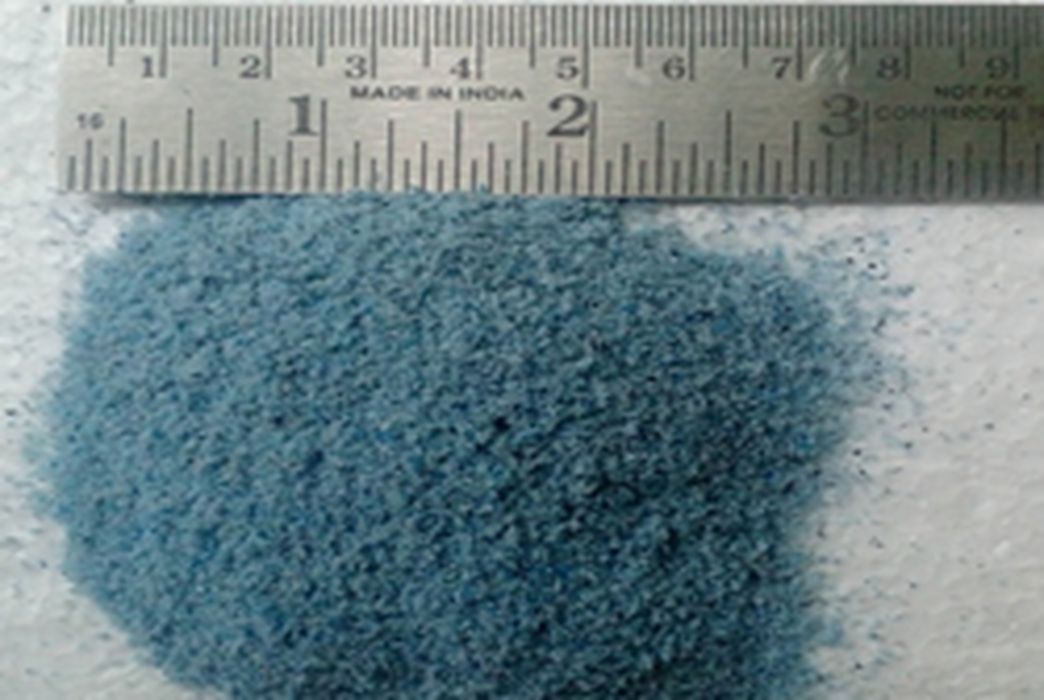

To explore this, the researchers collected sweat from 36 adults who wore absorbent pads in their armpits while they watched 30-minute clips of a horror movie, to induce fear, and a nature documentary, to induce calm. The researchers measured the senders' physiological traits and subjective feelings to categorize their level of fear from the horror movie as low, medium or high.

At the highest level of fear, individuals were emitting more sweat, which the authors said supports the idea that humans may express the degree of fear they experience in their sweat. Higher quantities of sweat also emitted more volatile odorant molecules, which are the organic chemicals responsible for body odor.

Thirty-one female adults were recruited to be receivers in the study, because women have a tendency for superior olfaction, or sense of smell, the authors said, and they "typically show larger effects of olfactory-induced emotional contagion."

Odors were delivered to the receivers using a custom-built, four-channel olfactometer controlled by a computer, operating in a way similar to how air circulation in the real world carries smells from the body or clothing to someone's nose. Participants were first asked to rate the intensity and pleasantness of four odors that the researchers had categorized as neutral, low fear, medium fear and high fear.

The structure of the main task involved the participants receiving a small quantity of odor a few seconds before being shown an image of a man's face that had been manipulated to display an ambiguous expression. They were told to choose whether the face displayed fear or disgust. While the participants performed the task, their breathing and cardiac activity were monitored, and their neural activity was measured with functional magnetic resonance imaging scans.

The researchers expected that as receivers were exposed to higher levels of fear sweat, they would perceive more fear in the ambiguous faces. However, this was not the case, as the levels of low, medium and high fear-sweat stimuli were indistinguishable to the receivers. And all levels of fear sweat skewed the participants toward perceiving fear in the faces.

But smelling the different doses of fear sweat did cause the receivers to partially pick up on the presence of fear in the sweat, as seen in their behavioral, physiological and neural levels. The amygdala and fusiform gyrus regions in the receivers, which activate during a fearful experience, were also activated by the smell of fear sweat emitted from another person.

"It is possible that each level of fear sweat transmitted by a sender, even at minute doses, activates high-affinity receptors early in the inhalation of a receiver, inducing fear-based behavior in the recipient," the authors said. "This temporal winner-takes-all principle could explain the functional benefit of a high-sensitivity system to elicit fear, ensuring that the receiver is safe rather than sorry."

The researchers noted that this constitutes new evidence that, despite the chemical complexity of odor stimuli, the human olfactory system is able to detect fear above a minimal threshold.

"Achieving this form of stability and simplicity is a remarkable feature of the human olfactory system, especially given the rapid fluctuations in odorant quantity and quality," the authors said. "That these odors can exert their functions beneath our conscious awareness underlines the potent yet unrecognized influence smells may have on our lives."

The study, "Titrating the Smell of Fear: Initial Evidence for Dose-Invariant Behavioral, Physiological, and Neural Responses," published March 22 in Psychological Science, was authored by Jasper de Groot, Radboud University and the University of Pennsylvania; Peter Kirk, University of Pennsylvania and University College London; and Jay Gottfried, University of Pennsylvania.